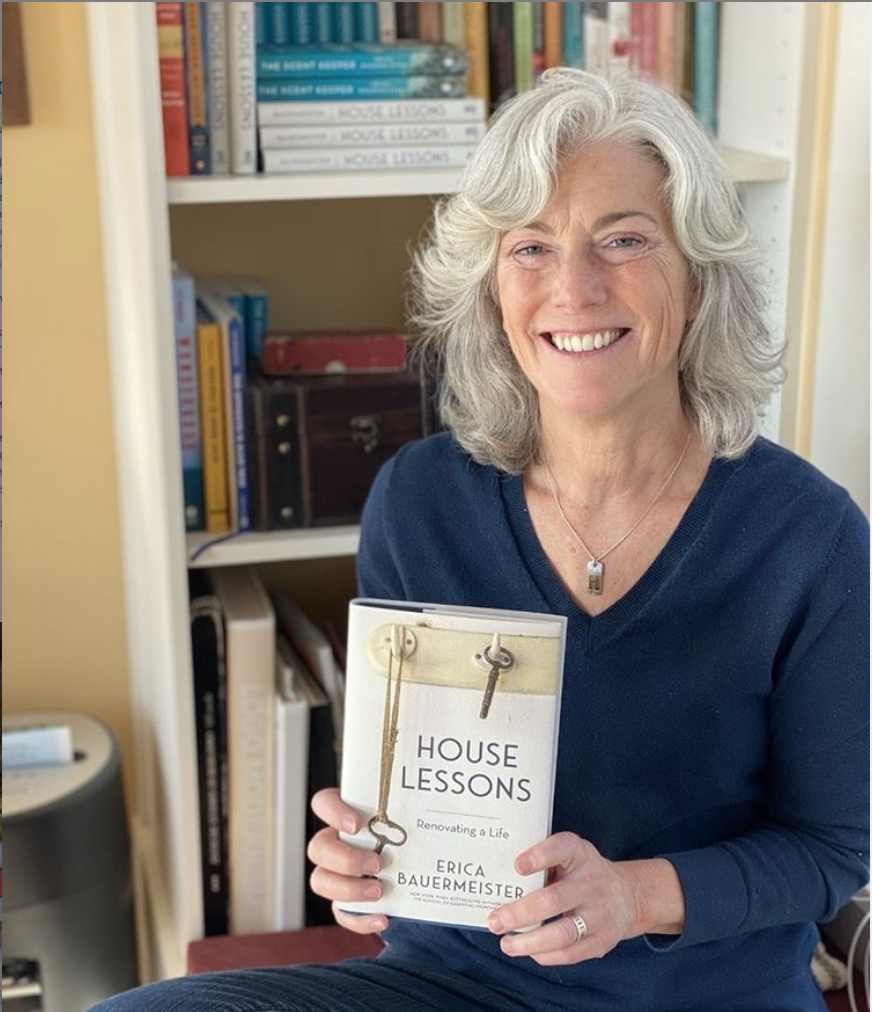

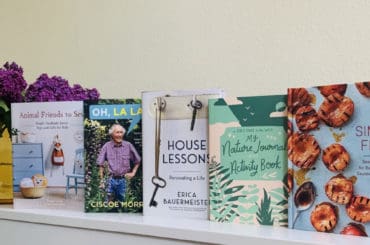

New York Times bestselling author of the novels The School of Essential Ingredients and The Scent Keeper, Erica Bauermeister published her first work of nonfiction with Sasquatch Books. House Lessons: Renovating a Life is a memoir-in-essays about the power of home, and the transformative act of restoring one very needy house in particular. It’s a personal, accessible, and literary exploration of the psychology of architecture, as well as a loving tribute to the connections we forge with the homes we care for and live in. It is also a story of a marriage, of family, and of the kind of roots that settle deep into your heart—designed for anyone who’s ever fallen head over heels for a house.

We talked to Bauermeister about the renovation, the 17 years that went into it (as well as the writing of the book), and how houses speak to—and reveal—the deepest parts of our psyche.

You bought a house filled with 7.5 tons of trash. Just about everything, from the foundation to the roof, had to be replaced. What did you see in it?

We humans have amazing emotional attachments to our homes, and it can hit you as hard and fast as a proverbial thunderbolt. And it usually happens with a house that is nothing like what you said you wanted. We were looking for land out in the country. Something simple that we could build on after we retired. And then drove up a hill in Port Townsend, WA and found the biggest, most rotten fixer in town and promptly fell in love with it. Why? I love American Four-Squares—their layouts are generous and open and bright. And they tend to have gorgeous front porches. So there was that. But in the end, the house just talked to me. It needed us. I could no more say no to it than that puppy in the pound that is due to be euthanized.

House Lessons is set in the Pacific Northwest, and you talk about the importance of geography when it comes to happiness. What draws you to the PNW?

I think we respond to places much like we respond to houses. We fall in love with what talks to us, and every person is different in what they need. I met a woman in the Midwest who told me that living near the ocean would feel claustrophobic for her; I feel exactly the opposite. I love the idea that there is an ocean nearby that nobody can populate. I love the rain and the seasons of the Pacific Northwest. I love the long light of the summers, and the short days of the winters just means I write more then. But mostly I love the geography, the way the water and the islands and the mainland curl around each other. It feels like a dance to me.

This book is about events that started 17 years ago. Why do you think it took you so long to write about them? How did it change?

I wrote this book four different ways over the years. The first time, it was as it was happening. And then I did it two more times, each version with more perspective—because honestly, we don’t really know the lessons we are learning while we are learning them. That comes later. Sometimes much later. But something else happened over those years. I began reading more about architectural theory and the psychology of space. The more I researched, the more I realized that while the events of our renovation were funny or scary or entertaining, it was the insights into houses and how we live in them that had the real power. So I changed it all up, and made this a memoir -in-essays. The book still follows the chronological process of the renovation, but at each stage, I get the chance to step back and look at the topics of foundations or fireplaces or kitchen design through the lenses of culture or history or architectural theory—you name it. The book just bloomed when I did that. I call it a liberal arts approach to memoir.

You and your husband switched roles during the process of renovating the house. What was that like? How did it impact your marriage?

It wasn’t easy. We’d done the “Leave it to Beaver” thing for 14 years at that point. But that had never been our intention. We’d always planned to share work and the kids; life just got in the way of that, and honestly, it’s easy to fall into patterns that your own parents and the media have been showing you all your life. But I was really ready to change, and Ben was working from home, so it was possible. Still, we had to promise ourselves that we wouldn’t second-guess each other. I was in charge of the work site, and he would be in charge of the kids. What we learned was that we had very different ideas of what was good or safe or smart. We cam close to catastrophe a couple times, but in the end, that switch was the best thing that could have happened to us. I needed to stretch my wings a bit. And the kids were hitting adolescence, and they needed to a parent who could let them do the same thing. It’s a second, important thread in the book—because we renovated our marriage along with the house.

You call yourself a renovator at heart. What does that mean to you?

A good renovator is someone whose creativity is sparked by limitations, because you have to work within the style and bones of the house that already exists. You can change things, but the guiding principle is respect for the original house. For example, you could swap out windows to make them more energy efficient, but you’d keep the style of the double-hung if that’s how they were originally. It’s the concept of working with the house, rather than working on it. I always say one way to know if you’re a renovator is to look at how you approach food. If you like to eat out all the time, you probably want a house that’s already finished. If you like to craft a meal from scratch, and do all the planning and shopping—you might be good at building a house from the ground up. But if you’re one of those people who loves to make a fabulous meal from leftovers—well then, you might have the temperament to be a good renovator.

There’s a quote from Winston Churchill in your book: “We shape our buildings, and then afterwards our buildings shape us.” What does this mean to you?

I’ve been fascinated by the psychology of space for as long as I can remember. I just felt different in different buildings. Some houses felt joyous, and others made you depressed. It wasn’t the furniture or the people necessarily. The house could be completely empty and still have the same effect. I wanted to know why that was, so I started reading and observing. One person I read was Christopher Alexander. He was an architect who spent a lot of time observing how people lived in their houses and came up with 253 architectural principles. For example—people are unlikely to use a deck that is less than six feet deep, and they won’t naturally go out into a courtyard that is closed on all four sides. People do, however, love window seats, and light at the end of hallways, and rooms that have windows on at least two sides. And porches make us happy—they give us a feeling of welcome and help you shed your public persona and become a private person. When we acknowledge that we actually become different people in different environments, the houses and schools and office buildings that we build can make us feel truly alive.

What would you tell your younger self now, if she was just finding that house?

That it will be more work than you can possibly imagine. That you are stronger and more capable than you think. That you will discover things about yourself and your family that you never expected. And while you may end up with a beautiful house, what you learn could never be contained within its walls—and that the house will teach you all of that.

To hear Erica read from the book, check out this video!

House Lessons: Renovating a Life is available wherever books are sold, in print, ebook, and audio formats.